Improving Unproctored Online Assessments: Simple Methods to Help Maintain Academic Integrity

Protecting the academic integrity of online assessments is a nontrivial task, particularly for high-enrollment courses where self-graded multiple-choice assessments are necessary. Proctoring services such as ProctorU are expensive and not error-free (e.g., they flag students who are looking down as they write out their work and cannot detect all instances of cheating), and may not always be necessary. While there is no perfect solution, some simple strategies can be used to deter cheating in online multiple-choice assessments. This can be accomplished in Moodle by: 1) creating multiple versions of each question, 2) scrambling the order of questions and answers, 3) setting timing parameters, and 4) having students upload their written work upon completion. The result is a no-cost and low-tech method for online assessments with higher academic integrity.

How to Create a Quality Multiple-Choice Assessment in Moodle

You may have created your own assessments before in Moodle and already know the basics. Here are some suggestions to improve an ordinary multiple-choice assessment by taking advantage of the settings and features available in Moodle. e-LIS offers help docs specifically for Moodle Quizzes, including one on Reducing Cheating in Moodle Quizzes.

Create a separate “category” for each question of your assessment.

Suppose you wish to create a 20-question exam. For each question you wish to include, create a “category” in the Moodle “Question Bank” and give it a helpful name so that you know what it represents. For example, “Q1: Temperature Scale Calculation” would be an example I might have for my General Chemistry course. Once you create one of the questions for that category, you can make additional versions by “copying” the question and editing it. Granted, this is more easily accomplished for calculations (where we can change numbers) rather than conceptual or factual information questions. The goal is to have at least two different versions of a very similar or identical question.

Build your “quiz” in Moodle by adding a “random question” from each category.

After you have created your “quiz” in Moodle, you can add each of your questions by clicking on “add” (at the bottom of the “edit quiz” screen) and choosing “a random question” from the drop-down list. Select the “category” you want and repeat this process until you have all of your questions included. The advantage of using explicit categories for each question rather than pulling a set of questions from one large database is that each student will have a very similar set with similar difficulty. For example, a simple definition is much easier than a challenging calculation or critical thinking question. Using the question category strategy helps avoid complaints about differences in difficulty levels for different students.

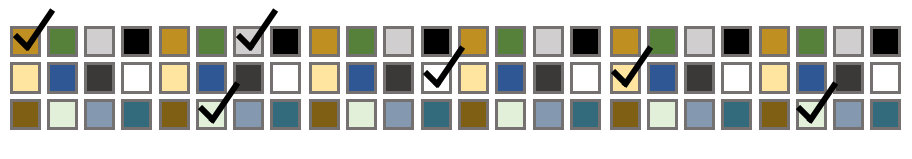

Check the “shuffle” box at the top.

This simple checkbox allows the questions to be scrambled in a different order for each student. In addition, you’ll want to make sure that your questions also have the “Shuffle the Choices” box checked if you want the answer choices to be shuffled.

Set the minimum time limit needed and a narrow window for synchronous availability.

When you choose the settings for “Timing,” only allow enough total time (i.e., the “Time limit” parameter) for students to complete the assessment as if you were in the classroom to reduce the likelihood of unauthorized resources or collaboration. That being said, provide extra time for students to login, solve potential tech issues, and begin (e.g., if the assessment length is 60 minutes, allow a 75-minute window of time).

If you teach a fully online course and would like students to start tests at the same time like they would in an on-campus environment, such required exam times have to be in the SAIL course description when students register for your course.

Create an ungraded “assignment” for students to upload their written work.

If your discipline would normally require written work to arrive at a final answer (e.g., for a calculation question), you can require that students submit a scanned copy of their handwritten work as an ungraded post-assessment assignment. Using the “assignment” tool in Moodle, you can restrict access until the assessment is marked “complete” (i.e., using the “Activity completion” setting). There are several free phone apps that allow students to scan their work and create a single PDF file to upload (e.g., Adobe Scan or Genius Scan work on both iPhones and Android devices). With a little coaching, students can become practiced at accomplishing this task. The ability to review a student’s written work increases integrity and also allows constructive feedback options.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Charlene Hayden is a Special Instructor in the Department of Chemistry at OU. Charlene teaches general chemistry, as well as her area of expertise, analytical chemistry. She has 24 years of experience working as an industrial research chemist at the GM Research & Development Center. In her spare time, she loves cooking, bird-watching, and gardening.

Edited and designed by Christina Moore, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC. View all CETL Weekly Teaching Tips.

FORWARD with Midsemester Reflection

To reflect is to look back to bring clarity in moving forward

~ Teach4Endurance

At this point in the semester, our energy may start to lag. To help keep up our motivation and our students, check in with support available. These FORWARD steps can help re-establish connection and priorities.

Check yourself and your students

Feelings. How am I feeling? Am I motivated to teach?

Outcomes. What are my goals for this class? Am I meeting my goals? What evidence do I have that students are learning?

Relationships. Are you connecting with your students? Am I making content relevant?

Workload. Did I accurately gauge my workload? The students? How is the class pace?

Actions. How are students behaving in class? Are they overwhelmed, motivated, interested?

Reach out. Do my students need additional support? Do they feel like they belong? Have I developed my own community for support?

Direction. Am I using strategies to help students learn? Am I creating barriers?

Things to remember

- Reflection now can make the next class smoother (see 15 Minutes to Improve Next Semester: Teaching Tip)

- Remind students about academic well-being resources and personal well-being resources

- Help students understand your grading policies

- Check important academic calendar dates, and prompt students to do the same. Remind all students of the last day to withdraw (for full-semester courses)

- Watch attendance and participation at key points in the semester, such as mid-semester and right after break weeks

- Be ready for last-minute questions on final grades, exams, extra credit

Check these out

- Small reflections can bring about big changes (e.g. How I Learned to Embrace the Awkward Silences to Promote Class Participation). When there is silence in discussion, you can prompt students to pause and write.

- Asking students to reflect mid semester can give you additional insight. Christina Moore and other OU colleagues have used this simple midsemester journal activity.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Sarah Hosch is the Faculty Director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning and a Special Instructor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Oakland University. She teaches all levels of biology coursework and her interests include evidence-based teaching practices to improve student learning gains and reduce equity gaps in gateway course success. Sarah loves exploring nature, cooking, and exercising.

Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

View all CETL Weekly Teaching Tips.

(1).jpg)

Normalizing and Promoting Academic Success Support

Support services such as peer tutoring and Supplemental Instruction have been associated with positive outcomes for students such as increased GPA, use of effective learning strategies and retention (Arco-Tirado et al., 2011; Reunheimer & McKenzie, 2011; Dawson et al., 2014). Unfortunately, many students who would greatly benefit from seeking support never do. For instance in one study, students with lower self-esteem regarded seeking help as more threatening (Karabenick & Knapp, 1991). Another study found that students who felt less comfortable in the university environment associated help-seeking behaviors with feelings of inadequacy and inferiority (Winograd & Rust, 2014). Because of this, the Academic Success Center (formerly The Tutoring Center) welcomes support from faculty in helping students understand the benefits of utilizing our various services.

For students who need assistance with course content, the center offers drop-in tutoring, Supplemental Instruction and study groups, with a focus on 1000 and 2000-level courses. In addition, students can receive one-on-one assistance with test preparation, organization, time management, study strategies, and other success-related topics through academic support appointments.

Ways to Partner with the Academic Success Center

Use destigmatizing language when introducing support services.

Students often associate seeking help as an admission that they are struggling. Proactively counter this association by sharing that asking for help is precisely what successful students (and people) do (Moore, 2019). While we certainly want to reach students who are underperforming in their courses, it is helpful when students see our services as a normal part of the learning process, and understand that tutoring and SI allow them the opportunity to actively discuss what they are learning with others. As opposed to stating, “If you have trouble, tutoring is available,” you might say, “Students who are successful in this course actively engage with the material and address questions that come up right away. Regular tutoring/SI attendance is highly recommended for your success.” If you would like to add a statement about the Academic Success Center to your syllabus or Moodle page, we have Sample Faculty Moodle Statements. CETL’s Syllabus Template also offers language on academic success support.

Invite staff to speak with your class, with strategic timing.

Our staff is available to visit your class and speak briefly about our services. We find that students are a more captive audience when they hear this information after receiving grades for an exam, as opposed to at the very beginning of the semester. If you are interested, you can request a presentation.

Refer students who need assistance with learning strategies.

Students’ difficulties often go beyond understanding course content, especially as they transition from high school to college. Many students do not yet understand how to be independent learners, how to think critically about information presented, and how to implement study strategies that lead to comprehension and retention. In addition, learning to manage multiple assignments, technologies and deadlines without the constant check-ins the high school environment provides is a large adjustment for many students. Students who are repeating a course are also in need of support, so they can reflect on their challenges and brainstorm new strategies. Because of this need, our professional staff is prepared to help students with study and time management skills through our academic support meetings. Students can be referred directly to our website to make an appointment or you may email us at [email protected] if you would like us to reach out to a student on your behalf.

Help us grow our team by identifying high-achieving students.

While we actively post our positions on Handshake, faculty are instrumental in helping recruit potential tutors and SI Leaders. Even students who perform very well may not see themselves as someone who could help others succeed. Your encouragement and support gives students a boost of confidence to apply. You can recommend students directly to us.

Quick Resources

We warmly welcome your feedback and suggestions as we all work together to support our students. You can find us at our new location in 1100 East Wilson Hall.

- ASC Website

- Tutoring schedule

- Supplemental Instruction schedule

- Academic Support Appointments

- Residential Support

- Study Resources for Students

- Request a visit to your classroom

- Recommend a future tutor/SI Leader

References

Arco-Tirado, J, Fernandez-Martin, F, & Fernandez-Balboa, J. The impact of a peer-tutoring program on quality standards in higher education. Higher Education, 62(6), 773–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9419-x

Dawson, P., van der Meer, J., Skalicky, J., & Cowley, K. (2014). On the effectiveness of Supplemental Instruction: A systematic review of Supplemental Instruction and peer-assisted study sessions literature between 2001 and 2010. Review of Educational Research, 84(4), 609–639. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314540007

Karabenick, S. A., & Knapp, J. R. (1991). Relationship of academic help seeking to the use of learning strategies and other instrumental achievement behavior in college students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.2.221

Moore, C. (2021, September 16). Asking for help shows strength, not weakness. CETL Teaching Tips blog. Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University.

Reinheimer, D, & McKenzie, K. (2011). The impact of tutoring on the academic success of undeclared students. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 41(2), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2011.10850340

Winograd, & Rust, J. P. (2014). Stigma, awareness of support services, and academic help-seeking among historically underrepresented first-year college students. The Learning Assistance Review, 19(2), 17.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Mariana Allushuski is an assistant director at the Academic Success Center. She helps students reflect on their academic habits and develop more effective learning and time management strategies. At the end of October, Mariana will be moving to a new role as Director of Academic Success at OUWB.

Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

100 Library Drive

Rochester, Michigan 48309-4479

(location map)

(248) 370-2751

[email protected]

.jpg)

Getting the Most Out of Faculty Feedback

Faculty Feedback, OU’s early alert system, is required in 0000 to 2000 level courses during the first six weeks of semester to inform students about instructor concerns regarding course attendance and performance. Faculty Feedback is effective for communicating with students when used proactively. It has the benefit of being official communication from the university that students take seriously but does not impact their grade. As shared in an earlier teaching tip, the timing of Faculty Feedback is critical, as are related actions instructors can take to supplement their feedback message. This teaching tip offers six practical uses for Faculty Feedback in conjunction with your course records and grading practices.

Faculty Feedback in the First Two Weeks: Attendance as a Key Indicator

The Office of the Provost recommends that Faculty Feedback be sent in the first two weeks of the semester for maximum effectiveness.

- I keep track of students’ in-person or online attendance beginning with the first day of class. If a student has an unexcused absence in the first two weeks, I send them Faculty Feedback regarding their attendance.

- I continue to track attendance throughout the semester. I identify students who have more than one unexcused absence during the six weeks Faculty Feedback is open and send them a message when I notice the problem. In other words, a student may receive a message about attendance as late as Week 6 if that is when their attendance problem occurred.

Selecting the Issue of Highest Importance

Faculty Feedback allows instructors to select one issue of highest importance for their message: Not Attending, Meet with Me, Struggling Academically, or Time Management. I select an issue as follows:

- Students who are absent typically also fail to submit assignments. In such cases, I have to decide between “not attending” and “time management.”

-

- I select “not attending” in Weeks 1-2 because this is when the Office of the Provost aims to identify students who are registered but not attending.

- If a student develops the double problem of poor attendance and missed assignments in later weeks, I select “time management” at that time because the student will begin to lose many points by failing to submit assignments.

- If attendance is not a problem but the student has missed even one assignment, I send a “time management” message. This alerts the student to the fact that they missed an assignment and need to watch course deadlines.

- I have multiple entries in the grade book each week beginning with Week 1, which allows me to see quickly if a student is struggling. Within the first few weeks of the course, I can detect an emerging pattern of poor performance, and I send a “struggling academically” message.

- I rarely send “meet with me” messages because they do not indicate the nature of the problem the student has in the course. I prefer the other three selections, which state the instructor’s concern more specifically.

Sending Two Faculty Feedback Messages

Although it is awkward to send two Faculty Feedback messages to the same student since the wording of the message template is fixed, if I find that a student who received a “not attending” message early in the semester later begins to miss assignments, I will send them a “time management” message. This also helps to address the common pattern of absences paired with missing assignments.

Students Following Up with You

Students are sometimes genuinely perplexed about why they received Faculty Feedback from me. They may not realize that my course has a mandatory attendance requirement, or they may have overlooked assignments on Moodle. When a student contacts me to follow up on Faculty Feedback, I am always willing to discuss further. The supplementary discussion we have is useful for helping students understand my course policies and what assignments they have missed.

Keeping Records of Faculty Feedback

Instructors receive an e-mailed report after sending Faculty Feedback. It is also useful to keep track of Faculty Feedback in the following ways:

- I keep a record of Faculty Feedback in the Moodle grade book. I use the feedback column in the grade book to indicate when I sent a particular student Faculty Feedback. I typically enter a note in the feedback cell for the assignment whose due date corresponds most closely to the time I sent Faculty Feedback. The note reminds the student they need to pay attention to my Faculty Feedback and also helps me keep track of students I am monitoring. (If you need help with any aspect of the Moodle grade book, set up a one-on-one consultation with e-LIS. Also see my teaching tip on the Moodle grade book.)

- I maintain a document with a running list of students who have received Faculty Feedback. I record the course, student’s name, date of the feedback, and the issue I selected. Since I usually teach multiple courses each semester, the list enables me to check quickly which students have received Faculty Feedback.

Assigning Final Grades

Sometimes students who perform poorly in the course contact me in an effort to raise their final grade. I do not change grades in response to such requests. Faculty Feedback is useful for showing the student they had a pattern of poor performance in my course. If a student received Faculty Feedback but continued to have problems in the course, I explain that I alerted them to issues with their course performance early on. This is also documented in the note I place in the Moodle grade book.

Conclusion

By using Faculty Feedback actively early on in the semester and throughout the six week period it is open, instructors gain a convenient tool to communicate with students about their course attendance and performance. Since Faculty Feedback is sent from the Office of the Provost, students are likely to see it as authoritative and may have a greater willingness to address their instructor’s concerns.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Helena Riha teaches Linguistics and International Studies. She has taught over 3,300 students at OU in 16 different courses and is currently developing a new online General Education course. Helena is the 2016 winner of the OU Excellence in Teaching Award. This is her fourteenth teaching tip. Outside of the classroom, Helena enjoys watching her sixth grader design his own Lego creations.

Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.