ChatGPT and Artificial Intelligence: A Lesson on Assessment Design and Talking with Students about Academic Integrity

Like many schools, we have spent much time facilitating discussions about academic integrity, or preventing and addressing various forms of cheating. While cheating has always been a part of formal education, it is hard to not get swept up in the ways technological advances increase these challenges. The current focus is on ChatGPT, an AI-powered chatbot that generates written text based on your prompts, from asking it questions to requesting it write an essay, lesson plan, or company statement. A websearch about ChatGPT will yield stories such as ChatGPT an MBA exam.

This teaching tip introduces how artificial intelligence, specifically ChatGPT, may change the way students engage with writing-based assessments and encourages all of us to explore it and design activities accordingly.

See how ChatGPT completes a course activity.

To get an idea of how this tool treats your writing assignments, enter your assignments’ directions into the ChatGPT bot to see what results it produces. If the results seem “passable” for the assignment, tweak the prompt or assignment description until ChatGPT produces a low quality result (illogical, too vague, etc.). Such tweaks might include:

- Referring to specific evidence via course texts, citations, and examples

- Applying the issue to a personal or local situation

Christina’s Example

I entered our writing department’s first-week writing prompt, which is meant to give instructors an early sense of students’ writing skills in case they may benefit from extra available support. The prompt presents a common societal issue, examples of different perspectives, and then asks the writer to explain their perspective, all in 450-600 words. Each time I regenerated a response (i.e. pressed the button for the AI to try it again), the response got longer, with the fourth time reaching 255 well-written, on-topic words. To the prompt’s credit, the AI response did not refer to the specific evidence presented. See my ChatGPT Simulation of WRT 1060 Prompt for the full examples. (OU Writing and Rhetoric professor Crystal VanKooten offers a link to more bot-produced essays below.)

Keep assigning writing, and build in space for assessing process.

While tech tools get more sophisticated and powerful, these issues have been around for decades. Even before widely available internet access, a student could always hire someone to do their writing assignments. Assessing students’ process can deter cheating by having students show you their work. This could be done through students submitting prewriting, reading notes, reflection, and works-in-progress. They could also meet with you to discuss their ideas. These don’t necessarily have to be closely reviewed or evaluated, but could be given credit as done/not done. I offer some of these potential checkpoints in Plagiarize-Proof Your Writing Assignments.

Make the writing multimodal.

In the guide Short-term Suggestions for AI Issues Cynthia Alby, education professor and author of Learning That Matters, suggests using “performance tasks” such as speeches, interviews, diagrams, peer instruction, and storyboards. Even if you teach a writing intensive course, writing could be derived from these other modes, such as the transcript for a podcast or interview, and written descriptions or annotations of visual texts. The world of writing is so much bigger than the kind of prose ChatGPT generates - and so much more fun! Writing is digital, multimodal, linked, and networked. It involves words, images, sources, and audio, it’s delivered via links and video, and it’s colorful and loud. When students are asked to work towards composing dynamic, multimodal writing for a motivating purpose, using an AI Text Generator fades away as even an option.

Consider using ChatGPT in class to discuss its results.

Show students what response it generates to course work, and ask them to analyze the quality of the response. Is it meaningful, or does it simply sound good? What do students offer as human writers that the computer does not? Are there writing tasks well-suited for a computer? (Who of us hasn’t benefited from spellcheck?)

If you do have students use and build on the bot’s writing in class, make sure you discuss the values and implications of doing so. What does using ChatGPT to write communicate about what the user values, and what our society values as a whole? If many writers used such a program to start their writing, what are some of the societal implications? What kinds of writing situations might ChatGPT writing be good for? In what kinds of writing situations would it be inappropriate or fail?

It is a rich opportunity to discuss rhetorical concepts such as context and purpose, which make the work of writing far richer than a sentence that sounds good. In their CETL Teaching Tip Beyond “Gotcha!” Proactive Plagiarism Pedagogy, OU’s Sherry Wynn Perdue and Melissa Vervinck promoted using these tools for pedagogical purposes rather than for surveillance.

From the Department of Writing and Rhetoric

Hi colleagues! This is Crystal VanKooten, chair of Writing and Rhetoric at OU. As a faculty member who studies writing and compositional practices and a follower of many writing teachers on Twitter and online, I’ve seen and heard many different responses to the recent advances in ChatGPT’s capabilities. These responses have ranged from sheer panic to bored indifference.

As Christina’s example above shows, ChatGPT will generate logical, error-free chunks of writing in response to a writing prompt. To read more of the bot’s prose, check out writing professor Anna Mills’ collection of sample AI-generated essays. Overall, the writing is….well, it’s ok! It’s not the most eloquent, original prose, but it’s on topic, grammatically correct, and communicates a discernible argument.

So as teachers who care about student writing and learning, what do we do? Do we need to stop assigning writing outside of class? Is this a moment of panic?

I don’t think so, and most experts in the teaching of writing don’t either. However, it is a moment to reflect on how and why we assign and assess writing in our courses. We can ask students to use writing to think and to learn, an approach to composition that doesn’t focus so much on the end product–those 255 words that the bot spits out. Students can show us their writing-to-think processes and demonstrate their learning through turning in notes and pre-writing, giving feedback to one another on assignments, composing and revising drafts, and reflecting in writing and via audio and video.

In addition to writing-to-learn and focusing on composition process, students must also write for specific audiences and purposes, when the end product itself is important. For these writing situations, Christina’s tips above will come in handy. There may be times when analyzing, critiquing, and even building on ChatGPT’s writing could lead to a better understanding of what works (and what doesn’t) in different writing contexts. Anna Mills has curated an extensive resource list on AI Text Generators and Teaching Writing on the Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse that provides links to articles, questions to consider, and strategies for mitigating harm to student learning for those who’d like to dig in more.

So my advice for other teachers is this: don’t panic, but do think critically about how and why students write in your class, and what you want them to take away from the writing experience that you design.

In Conclusion

Let’s see this as an opportunity to ask important questions about our role as educators and how to authentically engage students in learning. We’re happy to explore the possibilities with you: Meet with Us to review writing assessment strategies or overall create a learning environment in which everyone works to uphold academic integrity.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Authors

Written by Christina Moore, associate director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, and Crystal VanKooten, associate professor of Writing and Rhetoric at Oakland University. Image from Open AI’s ChatGPT. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

Knowing “Who’s in Class” Supports Inclusive Teaching

Inclusive teaching practices encourage us to intentionally create and nurture a learning environment that supports all students. From the moment we begin communicating with our class, we are shaping our relationship with our students and the classroom community. As inclusive educators, we establish a welcoming tone, use an equity-minded syllabus, give explicit learning outcomes and expectations, and we carefully craft our curriculum to support all learners. However, even with the best course planning, we can’t predict each class’s individual makeup and the barriers they may encounter in our class. Thus, we may not recognize these barriers and challenges until later in the semester, if at all. What if, instead of reacting to success barriers, we proactively meet the specific needs of the class at the very start?

In the book What Inclusive Instructors Do: Principles and Practices for Excellence in College Teaching, Tracie Addy presents a tool that instructors can use to better understand their students at the beginning of the semester. This anonymous and optional form was designed to provide students with the opportunity to share information about their social or cultural identity, and other information that may influence their success in the class. A study using this tool in a variety of courses indicates that both faculty and students found a benefit in its usage, including a way for students to provide the instructor with information that they normally would not have given.

The Who’s in Class Tool

The Who’s in Class tool includes simple “check all that apply” questions and short response questions. Questions can inform faculty about whether their students are commuting to campus, access to technology, social identities, financial barriers, and other information that may shape how students learn effectively. As an OU-specific variation of this tool, OU faculty can use the Getting to Know You form in OU’s Google Form templates, edit and add questions, then distribute it to their students.

Additional Ideas

- Offer free response prompts like “Tell me a little bit about yourself (major, interests, etc.), what you hope to get out of the class, and any concerns you might have for the semester ahead.” These can be done on a piece of paper on campus, or students can submit their pieces in a format other than text-based writing, such as audio or video.

- Past OU guest speaker Bryan Dewsbury asks students to write This I Believe essays in his large biology courses.

- Activities such as the Personal Identity Wheel can be effective and creative ways to learn about your students and build community.

Gathering information about your students starts the semester on a note of caring and support, and can provide faculty with information for establishing equitable teaching practices.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

Written by Sarah Hosch, Faculty Director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC

Building Community Differently

While many people are tired and still recovering from nearly three years of volatility, I recognize in myself and others the way we light up when we really feel connected to one another. We particularly appreciate our communities--whether they be our families, small groups of friends, organizations, offices, or groups united in purpose and larger goals. They remind us of why we do what we do.

In 2020 I passed along a range of community-building activities by Equity Unbound and OneHE that provide fresh ways to get people talking and think outside the box. They were customized for online purposes to keep people connected during COVID, but I still use them to think differently about how to get the most out of time together, whether they are classes or meetings. Here are a few different kinds of activities I have facilitated and how the groups responded to these activities.

Warm-Ups and Introductions

The simple prompts offered in “Tea Party” have been useful in the opening minutes leading up to a class or meeting, particularly in a Zoom chat. Even having people answer these questions for themselves can help focus individual and collective purpose for being together at that specific time.

- I am joining this session/taking this class because …

- Lately, my priority has been...

- A big opportunity I see for us is…

For new groups that will be working together over a semester or longer, try new ways for everyone to learn about one another, such as through Story of Your Name Introductions and Share an Object From Home. Both activities focus on one specific element of one’s experience and identity as a way to share a larger story of one’s self, which reminds us of the complex, unique people that comprise the class or other group.

Creativity and Idea-Generation

In the moments when few are talking and ideas have stalled, prompt the group to frame the situation differently. 15% solutions is one of my favorites, which invites us to “discover and focus on what each person has the freedom and resources to do now” make something 15% better. The activity brings big problems into an actionable scale. You can supply what the problem or opportunity is at it relates to your class content or committee work.

Quick drawing activities can prompt us to process a problem or idea differently. Especially during the winter months when we may feel less energized, such activities can help us process ideas differently.

While not drawing focused per se, Spiral Journal starts with a focused drawing and then short writing. Everyone divides a piece of paper into four quadrants, draws a slow, mindful spiral at the center, and responds to a different prompt for each quadrant. See slides used for Spiral Journal.

More drawing-focused, Tiny Demons/Drawing Monsters prompts us to identify four fears or anxieties, draw four “monsters,” and attach each to one of your fears/anxieties. Then, alter the drawings to reframe your perception of and approach to them.

When I did these activities with women in higher ed group they described both how it helped them process anxieties they had been holding onto and they immediately sensed their students would benefit in the same way. (See Drawing and Doodling for Learning and Community-Building: Gather Session.)

Closing

There is a growing desire to do things differently and reimagine learning and work that is more generative and purpose-driven. We may struggle to implement new routines, and using activities like this can be a small but powerful start. Equity Unbound and OneHE’s community building activities library includes many more activities you can browse, each with video demonstrations of how they work, step-by-step planning directions, and starter materials as needed.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

Written by Christina Moore, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University. Photo by Robert Katzki on Unsplash. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

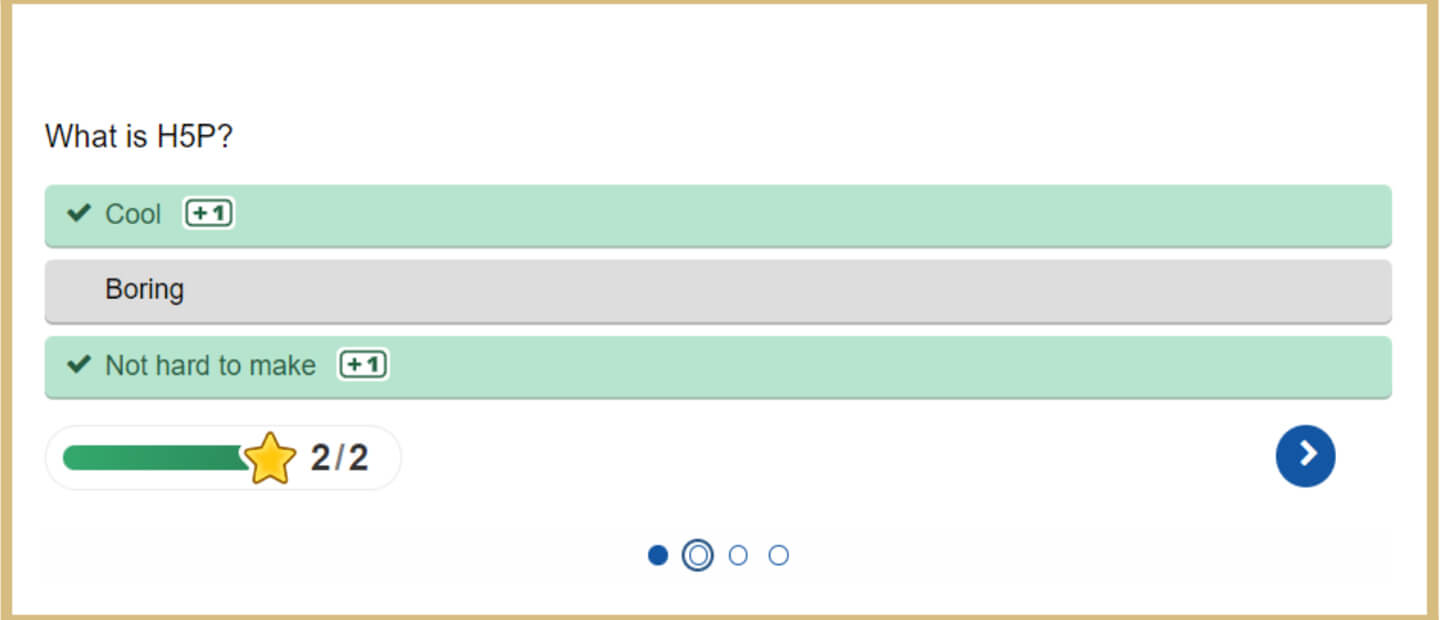

Quick & Easy Formative Assessments with H5P

Formative assessments are key for learning as they promote growth through practice and feedback. It can be a challenge to create assessments that are engaging and meaningful for students yet not too much work for the instructor.

If you want your students to do formative assessments throughout the semester at their own pace, H5P activities have a lot of different options. H5P activities such as interactive videos, clickable pictures, engaging quizzes and dozens more, are created directly in Moodle using the content bank. Once you have created your formative assessments via H5P, you can put them directly into a page, a book or an assignment in Moodle. One benefit of H5P activities for formative assessments is that instructors can add automated feedback to their activities so students can receive immediate feedback after completing an H5P activity.

If you need any assistance creating H5P activities for formative assessments, schedule a 1 on 1 with an Instructional Designer at e-LIS.

More on Formative Assessment

Formative assessment aims to keep track of student learning and provide continual feedback that both students and teachers can utilize to enhance their instruction. Formative assessments can: identify students’ areas of strength, weakness and improvement, assist educators in identifying learners’ areas of difficulty and taking prompt action to resolve issues.

In practice, formative assessments should be fast and easy for instructors to create and students to complete. Formative evaluations typically carry low or no point values because they are low-stakes tests or used as a method to gather information about students’ performance, knowledge or perspective of your course. These assessments can also be anonymous, which can be most beneficial when doing a formative assessment about students’ perceptions of an instructor’s course and how they are teaching the course.

Examples of Formative Assessment

- A short quiz or comprehension check after a concept, lecture or unit such as a multiple choice question, true false question or a question set

- A matching activity such as drag and drop or drag the words

- A hotspot image activity for students to identify pictures, components or concepts.

Conclusion

Formative assessments are a great way to check the pulse of your course and see where any learning gaps may be for your students. When it comes to creating formative assessments online, H5P is one of the most versatile tools instructors can use to check students’ understanding and receive feedback from them. Remember to assess early and assess often!

References and Resources

- Creating and Editing H5P Content e-LIS Help Video

- Adding H5P Content to Moodle e-LIS Help Video

- Adding H5P to your Moodle Course e-LIS Help Document

- For step-by-step guidance on getting the most out of the versatile suite of H5P activities, see e-LIS' H5p eSpace

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Chad Bousley is an Instructional Designer at e-LIS, who helps faculty with online course design, creating interactive activities and implementing online teaching best practices. Outside of the classroom, Chad enjoys learning foreign languages and playing guitar.

Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC. View all CETL Weekly Teaching Tips.

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

100 Library Drive

Rochester, Michigan 48309-4479

(location map)

(248) 370-2751

[email protected]