Collaborative Testing: Maintaining Rigor While Increasing Critical Thinking

After students complete individual examinations they form into small groups and take the same examination as a small group where they can discuss the questions and rationale for the answers.

How It Works

- Develop examinations, only need one copy of each examination. The class will use the same examination for the individual and group test.

- Develop groups, 5-6 students per group. Students can either self-select group members or faculty can assign groups. If students self-select, faculty then has the right to add students to groups that are not full to make sure that groups are evenly distributed.

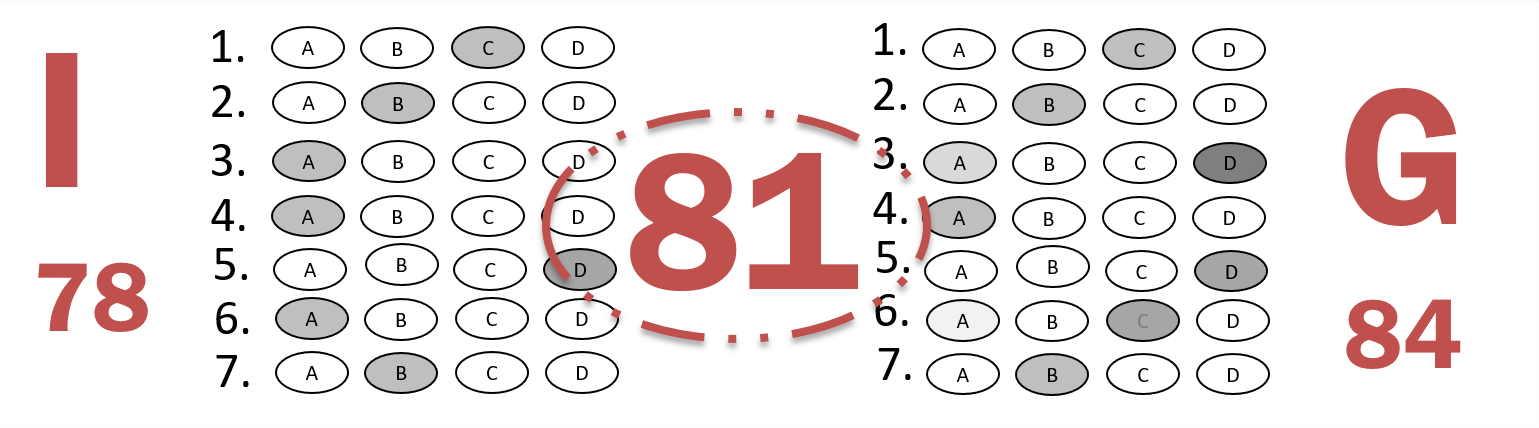

- Students take individual examination on their own using their own exam response sheets (traditional method to taking examinations, which is done via Akindi at OU). After completing examination, students hand in their sheets with an “I” (individual) at the top, leave the examination on their own desk face down, and wait in hall until the individual examination period is complete.

- Students return to classroom when faculty designates, take their own examination and a new exam response sheet to an identified location in the classroom for their small group. On the top of the sheet they put “G” (group).

- Students begin to take the examination as a group when faculty states it is time to begin and are given a designated time (usually an hour) to complete the examination. Each student can fill out the sheet with any answer they select; they do not have to choose what the group agrees upon.

- After completing the group examinations, as a group they hand in their scantrons and then wait until all participants have completed the group examinations. The students keep their examinations at their desks again face down.

- After the allotted time and all response sheets are handed in, the faculty then reviews the answers to the examination so all the students have immediate feedback on their performance. The instructor should stress that they still need to grade the examinations and will review using point-by-serial. If a question is deemed unclear and misleading, throw out the question. Their grade may be higher than what was indicated during the review.

Grading

- Grade the individual students’ grade on the examination.

- Grade the group grade for the student on the examination.

- If the student receives 78% or better on the individual examination, they are eligible for the group examination grade.

- Group examination grade is the average between the individual grade and the group grade.

- It is important to note that students MUST pass the class on their own individual grades for the examinations (70% overall) before any group grades are considered. They cannot pass the class because of group grades, but they can receive a better grade in the class because of the group grade so rigor is maintained while encouraging the objectives mentioned above.

- If an individual grade is higher than a group grade, the individual grade is the final grade. There are no negative consequences for taking group examinations and students have rarely refused to participate in the examination.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Adapted from an OU Instructional Fair presentation by OU Nursing’s Barbara Penprase, PhD, RN; Lynda Poly-Droulard, Ed.D., MSN, MEd, RN; and Marla Scafe, PhD. Edited and designed by Christina Moore, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University. Originally published March 24, 2014. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

Procrastination: Changing Small Habits Has Big Payoffs

Procrastination is too often perceived as an inevitable condition of university classes. Sometimes it is worn as a badge of honor, students bragging that they crammed work designed for a two-week work span into six hours. But students and faculty lose out on rich learning opportunities. Students are less likely to retain and transfer what they have learned: while cramming can result in the type of short-term memory required to score well on an exam, that knowledge is not solidified in a meaningful way (see the Small, Frequent Practice Makes Permanent teaching tip). Faculty can also be disappointed at a lack of depth in the work and connection to concepts covered across the semester.

The good news is that procrastination is predictable and can be rewired. We can also consider how course design can either encourage or prevent procrastination.

How to Undermine Procrastination in Learning

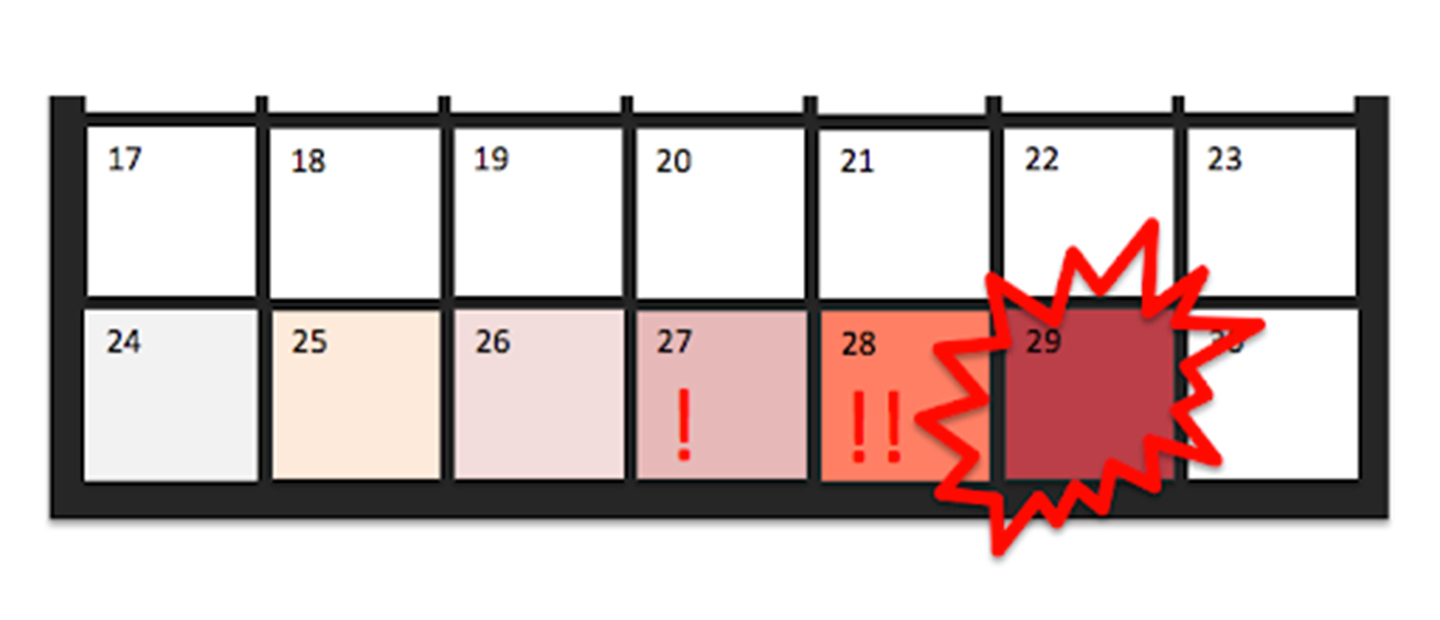

- Evaluate course design for procrastination traps.

College courses can set up students for procrastination’s grasp. By scaffolding larger projects with smaller checkpoints, or at least providing tips on how much progress students should be making, students will better sidestep procrastination traps. If you want students to practice this skill for themselves, prompt them to make a plan. Questions like these can help.

- How much time do you spend reading per week?

- How long is a typical study session?

- Invite students to use the Pomodoro Technique for getting started.

Procrastination makes it literally painful to start a task, especially if it is overwhelming in scope or difficulty. The Pomodoro Technique, which comes from a “tomato”-shaped timer, meets this challenge by encouraging students to spend a small amount of time on a task: “Just spend 20 minutes working on this part. That’s it! Anyone can work on this for 20 minutes!” This technique shifts the focus from product (finishing a 20-page research paper) to process (a set amount of time to identify which research studies on a similar topic relevant to the paper). Once students get going, they’ll be surprised that they are on a roll and don’t want to stop once the 20 minutes has expired. - Help students identify procrastination cues and rewards, and rewire them.

Habit loops are developed by a cue, routine, and reward. The procrastination cue is the stress of difficult work, which often leads to a routine of controllable tasks, such as browsing social media, checking messages, or cleaning. Ask students what new routines can replace these less-productive routines, such as the Pomodoro Technique or focusing on smaller tasks. Then, by placing a reward after this work, good habits are taking place! - Share your own trials and tribulations with procrastination.

Let’s admit it: some are procrastinators, and maybe even proud of it! While everyone has different learning and working preferences--and procrastination may sometimes work for some people sometimes--it is not a productive habit for sustaining high productivity and deep learning. Share with students your own cautionary tales of procrastination and how you work to prevent or harness procrastination.

Focused and Diffuse Modes, from OU’s Barbara Oakley’s Learning How to Learn MOOC

For more on the content presented in this CETL Teaching Tip, view the videos in Procrastination and Memory (Week 3) in the Learning How to Learn MOOC, featuring OU engineering professor Barbara Oakley and Terrence Sejnowski, UC San Diego biological studies professor.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Written and designed by Christina Moore, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University. Published May 2019. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

On Being Wrong: Cultivating Inclusion, Humility, and a Growth Mindset

“Good mistakes unlock learning because they focus our attention on a key step or insight that may have previously been out of focus. For mistakes to be good, a growth mindset is needed… a powerful way to foster a growth mindset in yourself and the people around you is to use language like ‘that was a good mistake.’ By normalizing mistakes as part of learning, we can nudge people away from an either/or mindset.”

- Dolly Chugh, from The Person You Mean to Be

While it seems obvious that we learn through trial and error, it is important that this trial and error be visible--not necessarily public and not in a highly visible and high stakes situation, but something we see before us as a mistake. Otherwise we suffer the illusion of fluency and competence: when we learn information that counteracts our previous thought, we convince ourselves that we really did know the answer. These illusions remove the impact of real learning, of seeing our growth and the real difference each class session can make in our understanding of the class content.

Many of our students experienced a high stakes learning environment in which high grades are everything and anything resembling failure is unacceptable. To unlearn this assumption that all failure is bad, that all mistakes are a result of our shortcomings, we should seize opportunities to normalize mistakes and being wrong. As Chugh explains, being able to say “that was a good mistake,” to our students and to ourselves, cultivates the growth mindset that is crucial to learning, creativity, and so many measures of capability. If we as the experts in our field, those on top of our game, can regularly tell our students stories about failure, mistakes, and growth, our students will have more to say and learn, and our classes will get a whole lot more exciting.

Prompts on Being Wrong

Dedicate a regular time to acknowledge, surface, and narrate mistakes (weekly, twice a month). By doing this, you create pathways for students to acknowledge, reflect on, and move beyond mistakes that might have otherwise blocked their motivation and concentration.

- Share your mistakes on your academic journey. I love faculty conversations where all of us share humble beginnings: bombing an exam, failing a class, switching fields, profound misunderstandings. We should be open to sharing these with students, along with how we grew and succeeded out of those moments. To emphasize with students that writing rarely, if ever, starts in great condition, I shared with my students a draft of my personal statement for graduate school, followed by a supportive, but candid review from my mentor who said he had no idea what I was talking about in the statement. I shared my initial reaction and embarrassment, then the resolve to slowly move toward improvements that led me to a much clearer final version. Doing this as a young, female professor can be risky, which is why showing the growth, skill, and career success that came out of that mistake is also crucial.

- Cite historic mistakes made in your field. Our fields are built on mistakes of all kinds, some that were valid at the time based on available data, others that were careless or the results of human error. These stories are not only surprising and engaging, but they also encourage critical thinking.

- Acknowledge current and ongoing mistakes in your field. It’s easy to dismiss the mistakes of the past, but we should also grapple with more recent and ongoing mistakes related to course material: frequent ethics violations, injustices, lack of equitable representation, distrust, toxicity. Acknowledge whose voices have been repressed and underrepresented in the discipline’s research and textbooks, followed by what is being done to correct this and how the class can contribute to this effort.

- Talking about fixed versus growth mindset. While it may seem like old news in the education realm, students may not have heard of Dweck’s research on the major effects of a fixed mindset versus growth mindset (see also Dweck’s TED Talk). The important message is that anyone can learn a skill, which is important for creating inclusive and successful environments for underrepresented groups (e.g. women internalizing ideas that they are “bad at math”).

- Commit to learning something with students throughout the semester. Professors have shared endearing stories of showing students that practice is required for learning any new skill. (I remember a story of a professor practicing shooting free throws throughout the semester and video-recording continual progress.) Pick something you would like to be better at, or let your students brainstorm ideas. This demonstrates the improvement process, but also helps minimize the “curse of expertise” that can create a gap between our teaching and their learning.

- Allot time for students to reflect on mistakes they’ve made and how they’d like to change that path. At a couple of points throughout the semester, prompt students to reflect on how they’re doing in the course, where they have made mistakes, and how they plan to grow accordingly. The Progress Report Journal is one example of how this can be done before the midsemester point.

- Create opportunities for students to experience mistakes in real time. During a class session, have activities in which students can immediately assess whether they were right or wrong about content related to your course, or answers that or more valid, relevant, or supported in the literature. These should resemble or build toward the type of assessments students will have, but in no-risk or low-risk situations.

- Praise a good mistake. I think the exact words Chugh (2017) uses are key: “That was a good mistake.” She goes on to explain the usefulness of this phrase when talking about mistakes made in having difficult conversations around identity or controversial topics. If students make mistakes that are in the right direction or that provide a valuable learning opportunity for the class, clearly state the usefulness of that mistake. This encourages risk-taking and growth beyond arriving at some “right” answer, which doesn’t always exist in our course work.

References and Resources

Chugh, D. (2018). The person you mean to be: How good people fight bias. New York: HarperCollins. Available at Oakland University’s Kresge Library.

Dweck, C.S., & Bempechat, J. (1983). Children's theories of intelligence: Implications for learning. In S. Paris, G. Olson, and H. Stevenson (Eds.) Learning and motivation in children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dweck, C. S.; Chiu, C. Y.; Hong, Y. Y. (1995). Implicit theories: Elaboration and extension of the model. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4): 322–333. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0604_12.

Save and adapt a Google Doc version of this teaching tip.

About the Author

Written by Christina Moore, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Oakland University. Image adapted from Rob Pym, Creative Commons Photos. Others may share and adapt under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC.

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

100 Library Drive

Rochester, Michigan 48309-4479

(location map)

(248) 370-2751

[email protected]