“What do you see?”

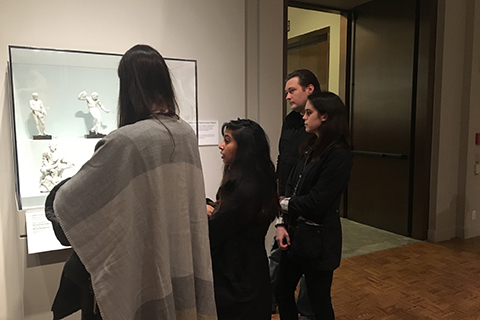

Mark Haimann, M.D. addresses a group of thoughtful medical students as they huddle before an exhibit at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA).

“It’s a sculpture of a man,” one explains. “He has no head.”

Haimann proceeds to ask students about the color of the sculpture, the medium with which it was made, and the similarities and differences of this sculpture to its cohorts in the exhibit.

The Careful Eye course invites OUWB’s M2 students to spend five consecutive Fridays at the DIA with their instructor Haimann, examining different mediums of artwork and discussing how their observations might translate to their careers in the medical field.

Each session focuses on a particular type of art – painting, sculpture – and follows a specific plan set by Haimann. He leads the group briskly from piece to piece, covering up the name and description of each work in order to avoid the students’ mind being steered in a certain direction. He calls on them by name to encourage each student to participate in the group discussion.

According to Haimann, the concept of putting medical students before art dates back to the 1990s, when a physician from Yale found that his residents became noticeably better at making observations about patients after asking them to describe detailed paintings in a museum. When OUWB opened its doors, Haimann – a life-long lover of art – proposed that they offer a similar course.

“We’re trying to help train the students to be very careful observers, to think about what they’re looking at,” said Haimann. “A subset of that is communicating what they’re seeing to other people.”

Brian Goldman, Class of 2020, entered the course with little knowledge of art, and left it with a newfound appreciation for detail.

“We focused a lot of time on small details in the works of art,” Goldman said. “As a physician, being able to notice and tease out small details in patients and their histories will be hugely important in understanding the patient and making a diagnosis.”

Further reasons for physicians to analyze artwork

In Haimann’s eyes, the purpose of future-physicians analyzing art goes beyond keen observation skills. In addition, the students learn the importance of being skeptical of both a piece of artwork’s description and a patient’s diagnosis, developing a better understanding of a patient or painting through listening to a backstory, and approaching difficult patients and difficult works of art.

“You’re not going to love every painting you see, just as you’re not going to love every patient you see,” Haimann said. “That doesn’t mean you can’t take very good care of the patient, and it doesn’t mean you can’t understand the piece of art.”

Students also enjoy the course because it gives them the opportunity to step outside of the classroom and engage in a creative outlet.

“During medical school, you spend so much time on your studies,” Goldman said. “While doing this, it can be easy to neglect things that would help make you a more well-rounded and cultured person. Having the opportunity to explore art with a medical perspective seemed like a perfect fit.”