Precision Health

‘A healthier and more equitable future’ through genetic screening

A genetic-screening project designed for adults is underway — and it not only has OUWB connections, but also holds a lot of promise to improve health care.

Richard Kennedy, Ph.D., associate dean for Research at OUWB, is program lead. (Kennedy also serves as vice president and director of Beaumont Research Institute at Corewell Health in southeast Michigan.)

Helping collect and monitor data is Ramin Homayouni, Ph.D., professor in the OUWB Department of Foundational Medical Studies and founding director of the school’s Population Health Informatics program.

Both are collaborating with Corewell Health, along with several other partners: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Mass General Brigham; Harvard Medical School; Ariadne Labs; Genomes2People; and Invitae.

The pilot program is offered at six Corewell Health primary care physician (PCP) offices. There aren’t any costs for participants — an important point because health insurance plans do not cover genetic-screening tests but may cover specific genetic tests if clinically indicated.

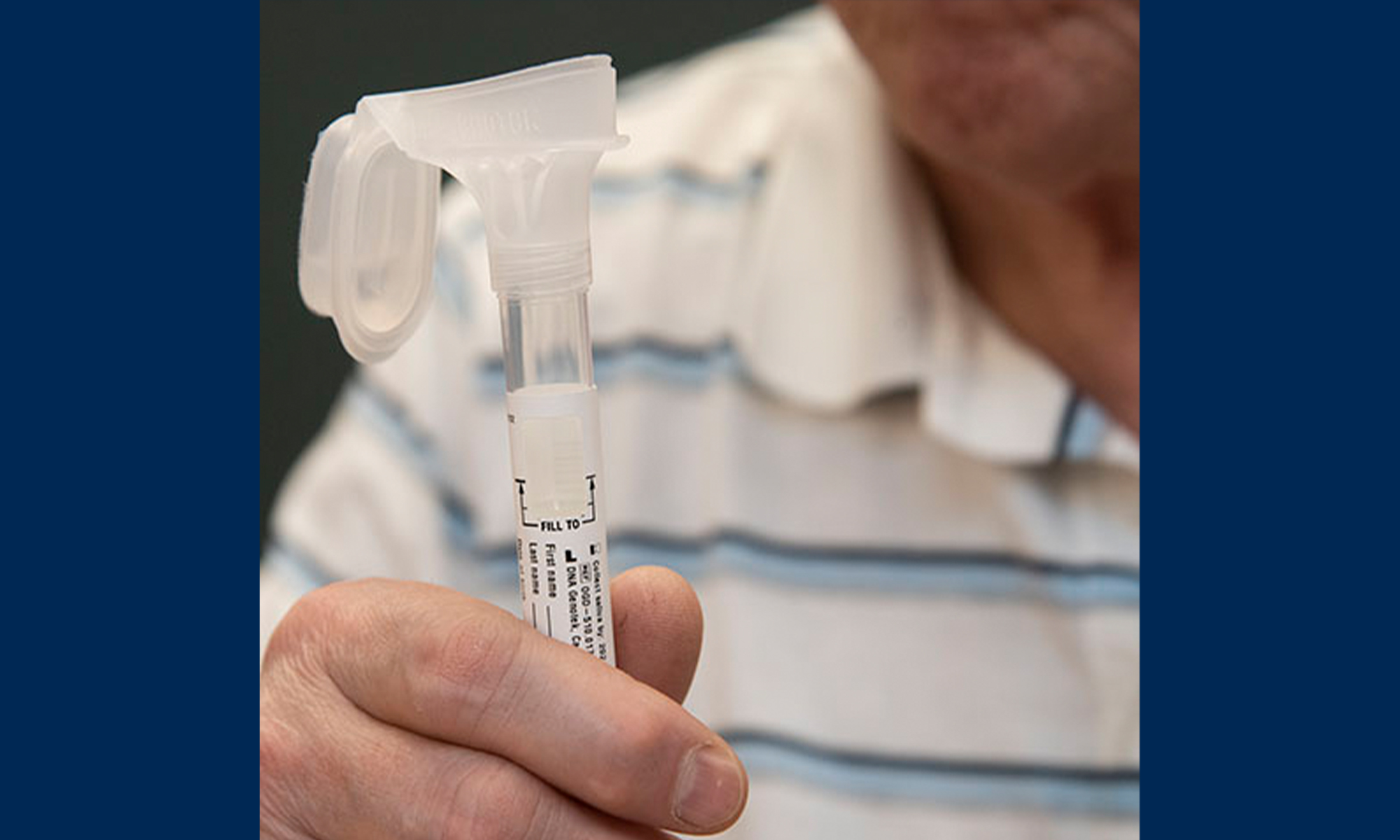

The process for obtaining saliva samples to test is simpler than an at-home COVID test. The sample is then shipped to Invitae for gene sequencing and the results are produced within a few weeks.

Unlike BabySeq, which creates a complete genome sequence, participating adults are screened for 147 genes linked to heart disease, cancer, and other types of treatable medical conditions. Knowing such information allows patients and their primary care physicians to create a customized prevention or care plan.

For example, a patient might have a genetic mutation that increases the risk for hypercholesterolemia, which means high cholesterol and a higher risk of heart attack or stroke.

“If health care providers know the genetic risk exists, they can make a plan for how aggressively they try to get cholesterol down,” says Homayouni.

Some patients are getting answers they’ve sought for decades. One individual was found to have a genetic mutation for a mild form of muscular dystrophy. Until the test, however, doctors were baffled by the patient’s unexplained disabilities, which prevented a definitive diagnosis and caused all sorts of complications in the person’s life.

Genetic screening also could be extremely useful for patients who don’t know their family history or individuals who were adopted and are not genetically related to their adopted family.

Still others are learning information that, in the future, could prove invaluable. Two parents each participated in a genetic screen and were found to be carriers of a gene that could cause blood clotting problems for their children.

“Seeing this come to fruition in real, practical manner that touches human life is tremendous,” says Homayouni.

Program leaders also aimed to test a diverse population with the office locations that were selected. They translated the patient materials into seven different languages, including Arabic, Spanish and Mandarin, as well as provided interpretation services.

The focus: creating a healthier and more equitable future.

“We want to show by being proactive and addressing health concerns early on, we can save money down the road and most importantly, improve the health of the community one patient at a time,” said Kennedy.

The first phase of testing consisted of 1,000 participants.

Program leaders have future plans of testing 10,000 patients and countless first-and-second-degree relatives over the next three years.

February 01, 2024

February 01, 2024

By Andrew Dietderich

By Andrew Dietderich