- YouTube

- TikTok

Tre… Due… Uno ... VAI!

Anthony Alú and his cousins rush throughout their grandparents backyard. Wearing their Sunday best, equipped with a hand shovel; the hunt for eggs was on. Easter egg hunts are not a tradition in Italy, but Anthony’s grandfather, Gioacchino “Jack” Alú, who was born in Canicatti, Sicily, wanted to make his grandchildren happy. The American tradition was lost in translation, though. Instead of hiding them throughout the house, Jack buried them in his backyard.

“We were dressed to the nines, right after church, looking for little piles of dirt,” Anthony explains. “Eventually, we found these giant balls of tin foil with a colored, hard-boiled egg inside.”

This memory is engrained in Anthony’s mind. He cannot tell you how many eggs he found, or who won, but he vividly remembers the smile that seemed cemented on his Nonno Jack’s face.

Memories like this, though, are scarce for Anthony.

“With him passing away when I was young, along with the language barrier,” says Anthony, “it wasn’t easy for us to make memories together.”

Because Jack only spoke Italian and Anthony only knew certain words or short phrases, the two were not able to hold conversations. Anthony never got to listen to his grandfather’s stories or learn about his past. And time to create more memories was coming to a close.

“He had been diagnosed with cancer and didn’t know how long he was going to live,” Anthony recalls.

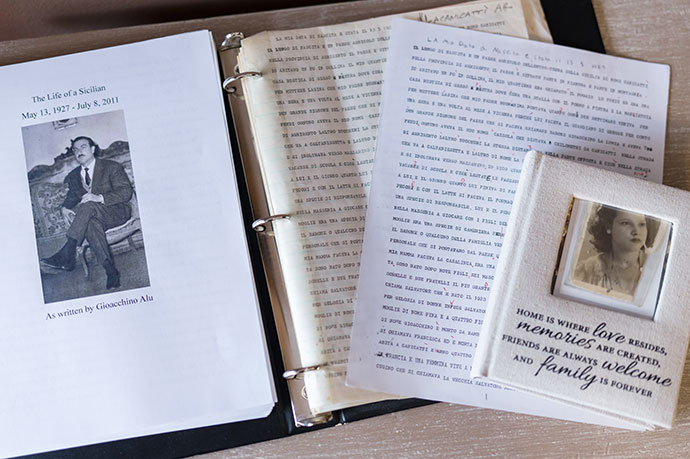

To ensure his legacy and allow his grandchildren to have a lasting relationship with him, Jack turned to a typewriter to document his life. Jack passed in 2011. But not before completing a 70-page memoir.

““It was different from what I was used to learning and hearing growing up,” Anthony says. “Nonno Jack created his own language, he would make spelling and grammatical errors, but they weren’t consistent, making it difficult. We had to get out of the mindset of true Italian and start thinking like him.””

DECODING HISTORY

In 2013, Anthony, while in high school, stumbled upon his grandfather’s story and was immediately enthralled. But, once again, the language barrier was an issue. Nonno Jack, who had a fifth-grade education, was not the most grammatically sound writer. The story was written in broken Italian, all caps and without any punctuation; it was, in a sense, a 70-page run-on sentence.

Anthony could not read Italian. His Italian-rooted family, however, jumped in to help. “They tried to translate it for me so I could write the story,” Anthony says. “We sat on the couch and tried it. But could barely get through a paragraph before my family started sobbing.”

The memoir struck a chord with the family. It was the first time hearing the stories since Jack had read the memoir before his passing. Hearing the incredible stories of his life again, brought back great memories.

“Jack lived an incredible life,” says Anthony’s mother, Teresa. “He was an amazing person and touched everybody’s lives.”

Anthony realized that he needed to learn more about the language in order to interpret the memoir and share Nonno Jack’s life. He enrolled at Oakland University, majoring in mechanical engineering. Choosing to minor in Italian languages, Anthony hoped to find a way to understand the memoir in order to reconnect with his grandfather.

During his second semester at OU, Anthony took a class taught by Special Lecturer Caterina Pieri, an Italian special lecturer for the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures. Anthony shared the memoir with Pieri, and the two established a process for translating: Pieri would read a chunk of the memoir aloud, the two would discuss what they believed Jack was writing and they would reconstruct the sentence in English.

“It was different from what I was used to learning and hearing growing up,” Anthony says. “Nonno Jack created his own language, he would make spelling and grammatical errors, but they weren’t consistent, making it difficult. We had to get out of the mindset of true Italian and start thinking like him.”

While reading the text word-for-word proved to be difficult and hard to understand, speaking the words was a quicker technique. “Italian is a phonetic language,” Pieri describes. “The way that Italians write is very consistent with what they pronounce. So, there were words that weren’t spelled correctly, but when you said them, they made sense.”

Anthony and Pieri were able to find some repetitions in Jack’s writing. One phrase was seen throughout the memoir: “e così,” which translates to “and so.” The pair eventually understood this to be the beginning of a new thought:

“Sapendo che mia mamma aveva paura delle armi e così ...”

English translation: Knowing that my mother was afraid of guns and so ...

JACK’S JOURNAL

Nonno Jack got right to the point with his stories.

On page 2 of the memoir, Jack detailed the brutal murder of his brother while they still lived in Sicily. Jack’s brother, Antonino, was helping a friend pen love letters to a woman out of town. As time went on and more letters were written, Antonino fell in love with the woman as well, and she with him. Antonino’s friend did not take kindly to this and plotted his murder. Jack’s brother was led into the woods, where he was shot and killed.

On pages 11-12, Jack described his time working on a local farm in Sicily during World War II, when he found himself stuck in the crossfire of a battle. Jack ran into the nearest house, where he hid with multiple families, to get shelter from the battle.

Boom. A mortar hit the building.

Jack’s body was flung into the air and crashed into the ceiling, knocking him unconscious. When he came to, Jack was wounded, his jaw and leg shredded by shrapnel. Realizing he was the lone survivor in the building, Jack crawled home. His body was so battered that his sister did not recognize him when he got back.

|

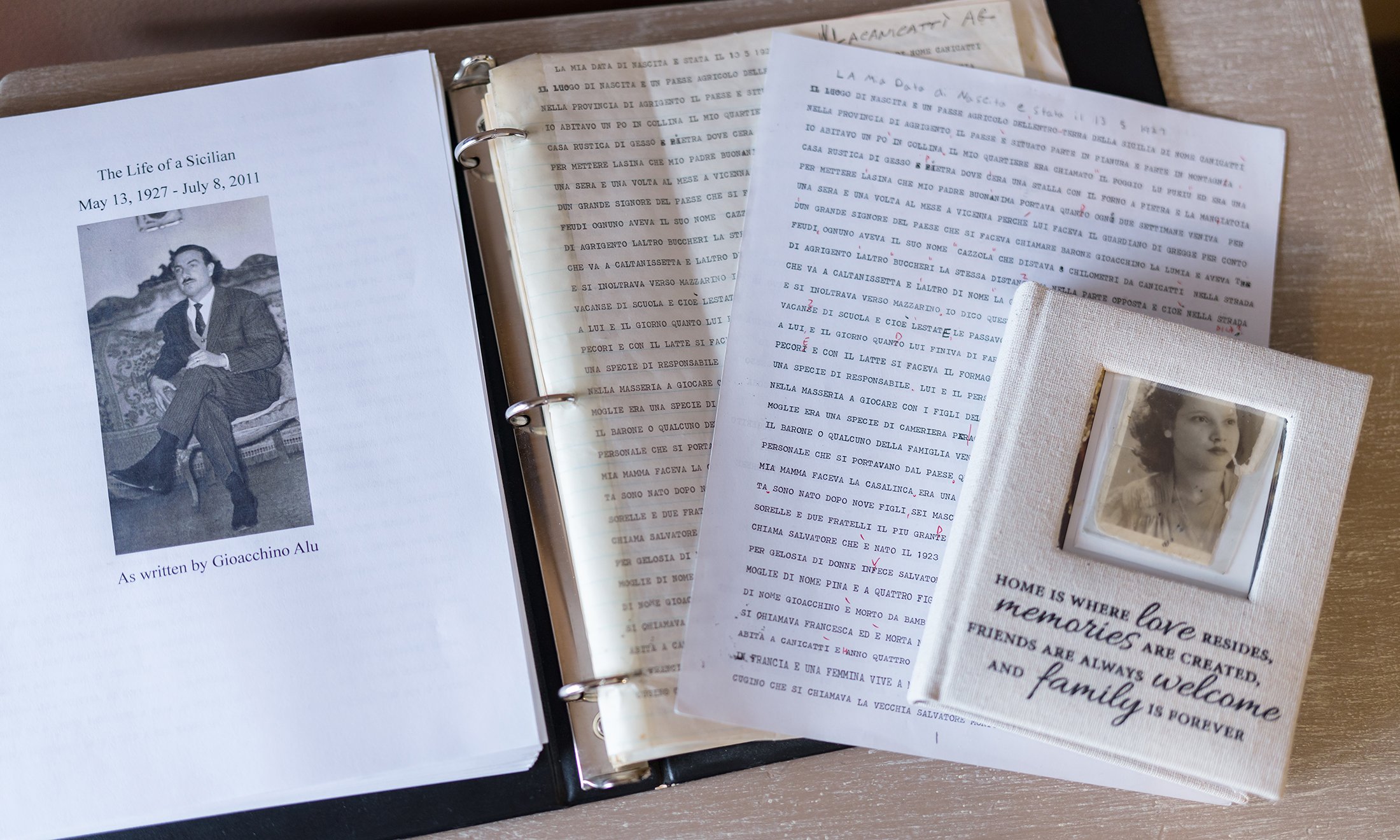

| The memoire that Jack wrote along side his photo and the photo of his wife, Rosa, that we kept with him until the day he died. |

On page 17, Jack recounted that, when he was 18 years old, a farming job brought him to an unfamiliar town for one night. Here, he crossed paths with a woman he described as “angelic.” He talked with this beautiful woman, and she gave him a photo of herself. Jack would continue to return to the town to see the woman, who would later become his wife, Anthony’s grandmother, Rosa. Jack carried that photo with him until he passed and the photo remains with the family today.

“He was definitely a fun-loving, family guy,” says Anthony, “I knew that when I was a kid, but you can really see that through his writing. I feel a lot closer to him. Through the translation, I feel like he was talking directly to me.”

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

The Alú family gathers at Anthony's home to celebrate Nonno Jack's memory.

RECONSTRUCTING ROOTS

After learning so much about his grandfather and the Alú family heritage, Anthony was compelled to visit Nonno Jack’s homeland. Luckily, a window of opportunity opened, as Oakland University offered a study abroad course in Italy. Anthony flew to Trieste, in northern Italy, and immersed himself in the history while practicing his Italian with locals. As the rest of the study abroad group flew back to the states, though, Anthony stayed to further explore Italy and connect with his relatives.

“I went to a little town called Sant’Elia, in the mountains by Monte Cassino,” Anthony says. “My aunts and cousins on my mom’s side still live on a farm there.”

In a similar situation with his grandfather, Anthony’s family did not speak English. Thankfully, this time around, he was prepared.

“By the end of the trip I was holding conversations with them,” explains Anthony. ”I was gone for almost two months, immersed in the Italian language and culture. I was able to speak with my aunts and cousins, who I had met for the first time, which was amazing.”

After Sant’Elia, Anthony travelled south to Sicily, where his parents and brother flew in to join him. Even though it was his first time stepping foot on the island, he was overcome with a feeling of home. Through his grandfather’s stories, he had a sense of familiarity with the land. And, despite Sicily’s demographic changing over the years, the Alu’s were able to visit areas that were mentioned in the memoir, including Nonno Jack’s home.

“We went to the house he lived in for a majority of his life,” Anthony says. “That was the house that my dad lived in until he was four or five. It was interesting because they had an iron sign made with my great grandfather’s initials, which was the same as my grandfather’s initials on it, still hanging on the house.”

Anthony’s father was finally able to show off the house he would kick a soccer ball off of; the hill that the ball would roll down; and the window it would eventually crash into and shatter. An infamous story that Anthony had heard millions of times.

Gazing upon his grandfather’s old stomping grounds, embracing the Sicilian culture and speaking Italian with lost relatives: these and an abundance of other moments have joined the Easter egg hunt; memories that, thanks to Nonno Jack, have strengthened Anthony’s family bond.

Explore other multicultural experiences in the Department of Modern Languages and Literature.

June 22, 2020

June 22, 2020 By Michael Downes

By Michael Downes