Communities create connections. From neighborhood book clubs to ideological movements, communities offer like-minded people an opportunity to unite over a common thread. But while this can connect some, it can also become a barrier for others.

“The complexity of building community is that as you unify you also run into the things that divide you,” says Jo Reger, Ph.D., Oakland University faculty and scholar of grassroots activism. “In my current research, what I’m really interested in is how a group of people try to build a utopian community in which they are valued, but in the course of doing so they also begin to run into the ways in which they are fracturing the community with some of their beliefs and ideas.”

|

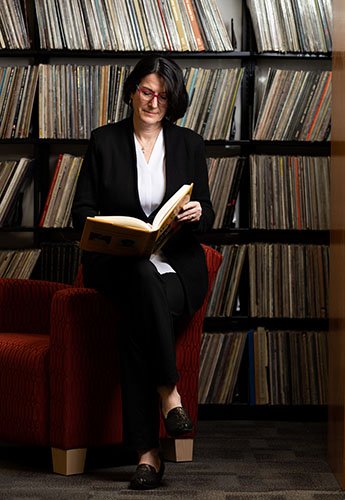

As a feminist researcher, sociology professor and the chair of OU’s Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Social Work and Criminal Justice, Dr. Reger’s research explores community formation, development and fracture, primarily in social movements and gender. She spent her early research years answering ‘What is the state of U.S. feminism?’ and addressed this question in her book “Everywhere and Nowhere: Contemporary Feminism in the United States.” In this research, she conducted an ethnographic analysis of three communities of young feminists, examining the movement’s continuity, intergenerational conflict, struggles with oppression and privilege, identities around sex, sexuality and gender, and strategy and tactics.

“I found that feminists in hostile environments sought alliances with older feminists and were moderate in their strategies and tactics in an attempt to survive,” says Dr. Reger. “In contrast, feminists in supportive environments often turned against older generations of feminists, seeing them as ‘out of touch’ and linked their feminism to a variety of causes, submerging it within other movements. I return to these issues of place, community and activism in my current project.”

In this new project — “Singing to Utopia: Lesbians, Feminists and Music, 1968–1998” — Dr. Reger explores the U.S. women’s music community and the formations and fractures within this culture.

She found that some women were being excluded from the mainstream music scene, among other groups, which indirectly gave rise to a vibrant women’s music community.

|

“Lesbians in mainstream feminist organizations, such as the National Organization for Women (NOW), found themselves marginalized and were declared a distraction from women’s liberation. At the same time, white lesbians, along with lesbians and gay men of color, found themselves shut out of white gay male organizations. The pop music scene of the 1970s, like the decades that preceded it, largely featured male musicians with few women achieving similar levels of success,” Dr. Reger explains.

Drawing from archival research, Dr. Reger analyzes written documents, news articles, meeting notes and vinyl records to tell the story of the women’s music community that was “forged out of prejudice and discrimination, but ultimately failed to create a space of equality for all,” she says. One such type of archival research is the content analysis of vinyl records associated with this underground women’s movement. Working with OU undergraduate student, Sam Heinz, Dr. Reger studies and codes the lyrics line by line, looking for issues of pride, resistance, utopia and community, among other themes. Additionally, Heinz also listens to the music to get a sense of the emotion behind the lyrics — a notion Dr. Reger also shares.

“Some of this music I know, so it brings back memories,” Dr. Reger says. “But other music makes me think about what it felt like to hear these songs and play these albums at a time when claiming a lesbian identity was taboo. I try to put myself in that time period for the women that bought the albums. Also, some of the albums have written notes on them and names which adds an extra layer of connection.”

The conception of this new feminist/lesbian music culture grew into a nationwide community that was anchored by ongoing music festivals, including the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival — a feminist event held in Oceana County, Michigan that ran annually from 1976–2015. The festival offered more than musical performances, but a space of camaraderie with workshops, art shows, dance and camping. This community of women provided a space of inclusivity for feminists and lesbians that otherwise didn’t exist, and participants built strong boundaries between themselves and the rest of society. “The result was a community of thousands of women that were largely invisible to mainstream culture,” Dr. Reger says.

|

By creating this culture, however, the women’s music community also developed barriers that excluded other marginalized groups. The community held a woman-born-woman philosophy that privileged cisgender women while rejecting trans women and men from festivals and events. “The community, particularly at festivals, that adopted this philosophy were labeled as transphobic and out of touch with the times,” says Dr. Reger. “While remnants of the community remain today, it has largely disappeared.”

“I find that the women’s music community of the late 1960s until the 1990s was an attempt to build a utopian community that provided safety and acceptance for a marginalized population,” she continues. “Yet within the safe space, there were forces that fractured that sense of utopia with some members privileged over others. I think this is key to thinking about the world we currently live in. At its core, my current project explores how the forces that unite some can become barriers to others. This dynamic is particularly relevant in these polarized, political times.”

Explore more unique research projects.

May 17, 2021

May 17, 2021 By Kelli M. Warshefski

By Kelli M. Warshefski